As plant-based diets gain popularity, so do myths about certain compounds found in plant foods—specifically phytates and oxalates. These compounds are often labeled as “anti-nutrients” and have sparked fear among some. But how much of this fear is justified? In this article, we’ll dive into what phytates and oxalates are, their potential impact, and simple ways to reduce anti-nutrients in food, ensuring you enjoy the full benefits of a plant-based diet.

Table of contents

What Are Anti-Nutrients?

I bet you’ve heard someone talking about phytates or anti-nutrients found in beans, grains, nuts, and seeds and how these reduce the body’s ability to absorb essential nutrients. Those compounds are called tannins, lectins, protease inhibitors, and calcium oxalate.

Let’s dive deeper into phytates and oxalates.

What Are Phytates and Should You Be Worried?

Phytates, or phytic acid, are naturally occurring compounds found in plant seeds. They serve as a storage form of phosphorus for the plant. They most definitely can be a problem. And the answer lies in their chelating properties. “Chelation” just means the binding of a metal ion to an organic molecule. So, when you eat food that contains a mineral like zinc, iron, or calcium, and you also consume phytic acid, the phytic acid will bind to — or chelate — the mineral, forming one of the phytates. Phytic acid and phytate are sometimes used interchangeably to refer to this chelation process.

What’s the issue with that? Our bodies lack the enzyme that breaks down phytates, so we can’t properly digest and absorb the nutrients that are bound up in them. That’s what the “anti-nutrient” label is all about.

For example, one study showed that when there’s phytic acid only 13% of magnesium and 23% of zinc were absorbed, as opposed to 30% when there was no phytic acid.

You shouldn’t be worried though. A 1994 review of trace elements in vegetarian diets from around the world didn’t find iron or zinc deficiencies in those people eating high concentrations of foods containing phytic acid.

How can that be? The thing is, by the time most foods high in phytic acid get to our plate, they may no longer contain enough of them to cause problems.

Health Benefits of Phytates

And a less known fact is that phytates may actually have health benefits. For example, they may reduce the risk of cancer, prevent heavy metal toxicity, act as an antioxidant, protect against kidney stones, help your body produce inositol that helps your liver process fats and has a role in muscle function. In addition, they may help to lower blood triglyceride levels, blood pressure, and blood sugar.

Who Should be Cautious of Phytates?

Still, there are certain groups of people who would benefit from knowing where phytic acid is most present in their diet and understanding how to limit it. Those are individuals who are at high risk for nutritional deficiencies and related disorders. Conditions like osteoporosis with calcium deficiency, anemia with iron deficiency, or zinc deficiency. Then, individuals who have malabsorption disorders and who are at higher risk of malnutrition. This may include people who suffer from an eating disorder or who lack access to adequate food.

Foods High in Phytates

Phytates are found in a variety of plant-based foods, including:

- Legumes: Black beans, pinto beans, kidney beans, soybeans, peanuts, and lentils.

- Whole grains: Brown rice, oats, and wheat.

- Nuts and seeds: Walnuts, pine nuts, almonds, and sesame seeds.

- Tubers: Potatoes, turnips, beets, and carrots.

These foods are nutrient powerhouses, so you shouldn’t let the presence of phytates scare you away.

What Are Oxalates?

Oxalates, or oxalic acid, are compounds found in many plant-based foods. Similar to phytates, they can bind to minerals like calcium and form insoluble compounds. While high oxalate intake can contribute to kidney stones in susceptible individuals, most people tolerate oxalates without issues.

In plants, oxalate helps to get rid of extra calcium by binding with it. That is why so many high-oxalate foods are from plants. As oxalates pass through the intestines, they can, also in our bodies, bind with calcium and be excreted in the stool. And when too many oxalates continue through to the kidneys, kidney stones can form. You don’t need to worry though as a study found that there was no increased risk of stone formation with higher vegetable intake. On the contrary, greater intake of fruits and vegetables was associated with a reduced risk.

Concerns With Oxalates

However, there is one food you could be conscious about, and that’s turmeric. Too much of it may increase the risk of certain kidney stones.

It’s because turmeric is high in soluble oxalates, which can bind to calcium and cause the most common form of kidney stone—insoluble calcium oxalate, and that’s about 75 percent of all cases. So, those who have a tendency to form those stones should probably eat no more than a teaspoon of turmeric daily.

You can also have increased oxalate levels if you’re taking antibiotics or have a history of digestive disease. It’s because, the good bacteria in the gut help get rid of oxalate, and when the levels of these bacteria are low, higher amounts of oxalate can be absorbed.

Foods High in Oxalates

Common high-oxalate foods include:

- Fruits: berries, kiwis, figs, and purple grapes.

- Vegetables: potatoes, green beans, rhubarb, leeks, spinach, beets, swiss chard.

- Nuts: almonds, pecans, cashews, sesame seeds and tahini, peanuts.

- Legumes: soy products, broad beans, black beans.

- Grains: amaranth, buckwheat, rye, wheat bran, quinoa, whole wheat.

- Other: cacao, black tea.

While these foods are nutrient-rich, consuming them in balance is key.

Soy and Oxalates

Now, I mentioned soy containing oxalates. However, this needs some clarification.

While tofu does have moderate amounts of oxalate it also has calcium that reduces the oxalate effects.

Moreover, soy contains phytates which inhibit the formation of calcium kidney stones. One study concluded that soy foods containing small concentrations of oxalate and moderate concentrations of phytate may be advantageous for kidney stone patients or persons with a high risk of kidney stones.

As calcium negates the effects of oxalates, opt for calcium-set tofu that is coagulated with either calcium sulphate or chloride.

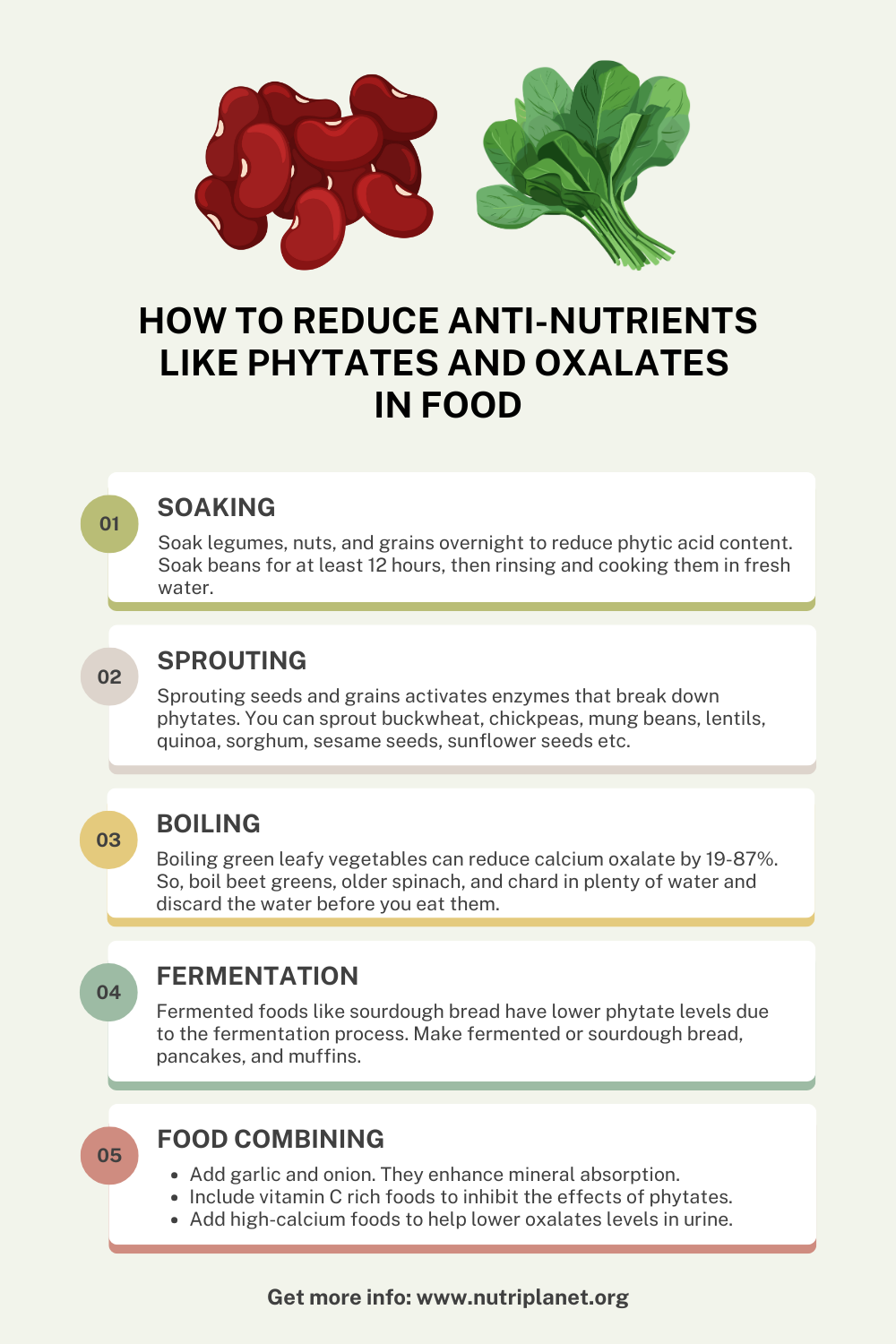

How to Reduce Anti-Nutrients in Food

Thankfully, sprouting, cooking, baking, processing, boiling, soaking, and fermenting all help to destroy phytic acid, oxalates, and other anti-nutrients and make minerals more available.

Soaking

Soak legumes, nuts, and grains overnight to reduce phytic acid content. It’s because most of the anti-nutrients in these foods are found in the skin. Since many of them are water-soluble, they simply dissolve when foods are soaked.

One study found that pre-soaking reduced the phytic acid concentration in quinoa by about 70%. In addition, iron solubility doubled as well. In general, soaking beans for at least 12 hours, then rinsing and cooking them in fresh water, reduces phytic acid levels by 60%. What’s more, soaking can even boost vitamin B content in foods.

Sprouting

Sprouting seeds and grains activates enzymes that break down phytates.

Research indicates that when we take white sorghum, sprouting and lactic acid fermentation can almost completely eliminate phytic acid. Overall, sprouting reduces phytates by 37-81% in various types of grains and legumes.

Learn how to sprout and cook chickpeas and how to sprout buckwheat. And here’s a great omelette recipe made with sprouted chickpeas.

Fermenting

Fermented foods like sourdough bread have lower phytate levels due to the fermentation process. Research has found that sourdough fermentation reduced phytates by 62%.

Learn how to make a basic sourdough, fermented buckwheat bead and sourdough spelt bread. You can even go one step further and prepare sourdough pancakes.

Boiling

Boiling green leafy vegetables can reduce calcium oxalate by 19-87%. This is why I would recommend boiling beet greens, older spinach, and chard in plenty of water and discarding the water before you eat them. Boiling is also a good way to reduce other anti-nutrients in your food like lectins, tannins, and protease inhibitors. For more details, go to How to Cook Vegetables to Retain Nutrients.

Food Combining to Reduce Anti-Nutrients in Food

Food combining is another way to reduce anti-nutrients in food. For example, garlic and onions can increase the bioavailability of iron and zinc in plant foods as they enhance mineral absorption. So, adding onion and garlic to your main meals is the way to go.

Another way to boost iron absorption and inhibit the effects of phytates is including vitamin C foods to your high-phytate meals.

Increase your calcium intake when eating foods with oxalate as it can help lower oxalate levels in the urine. Choose high-calcium foods like broccoli, watercress, kale, okra, chickpeas, and kidney beans. There was a study that tested how the addition of calcium may reduce oxalate in spinach. They compared calcium carbonate, chloride, citrate, and sulphate. And found that calcium chloride was the most effective while calcium carbonate was the least effective.

By incorporating these techniques, you can maximise mineral absorption and reduce anti-nutrients in food.

Summary and Main Takeaways

Anti-nutrients like phytates and oxalates have gained a bad reputation, but they are not as harmful as some suggest. These compounds are naturally present in many plant-based foods that provide essential nutrients. The key lies in preparation methods—soaking, sprouting, fermenting, and boiling can effectively reduce these compounds, ensuring you reap all the benefits without concern.

Remember, a balanced diet is about variety. Phytates and oxalates shouldn’t deter you from enjoying a wholesome, plant-based lifestyle. Equip yourself with knowledge, apply simple preparation techniques, and you’ll thrive on your plant-powered journey!

I have the genetic variation of non-secretor (of blood type into the tissues) (Lewis gene), which affects 20% of the population at large. What this means is that I cannot break down phytic acid, and it combines with calcium and magnesium and flushes it out of my system. Result? I have had cavities and root canals my whole life, until I found out about this genetic variation. I have tried soaking, sprouting and fermenting, but I found I still had teeth problems, and also, when fermenting, I almost passed out from the ferment and it’s effects. I also am pitta dosha (ayurveda), and so, I am not supposed to be eating fermented foods as it aggravates pitta. But I very much need the astringency of the beans, whole grains, etc. I have been very much seeking an answer to my dilemma.

Hi! Wow! I had never heard of this! Thank you for sharing! I hope you can figure something out! I’m sure there a specialists out there who have an idea how to address one’s diet with this condition. 💚